Latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) show significant increases in illnesses caused by group A streptococcal infection. During week 46 of the 2022/2023 season (which runs from mid-September to mid-September), there were 851 cases of scarlet fever notification and consultations reported, compared with an average of 186 in preceding years. The rate of invasive group A streptococcus (iGAS) infection is also currently higher than levels reported before the COVID-19 pandemic[1].

The increase in scarlet fever notifications also shows regional variation (see ‘Is the current rise in cases in children being investigated?’)[1].

Although deaths from group A streptococcus infection are rare, at the time of writing there have been 15 deaths in the UK since September 2022[2].

This article gives a brief overview of the latest information on seasonal activity of Group A streptococcal infection in the UK and will be updated periodically. It provides answers to the following questions:

- What is group A streptococcus?

- What illnesses are caused by group A streptococcal infection?

- How are group A streptococci infections spread?

- What are the symptoms of infection?

- What is scarlet fever?

- How is diagnosis confirmed?

- Who is at increased risk of invasive group A streptococcal disease?

- What treatment is available?

- Is the use of chemoprophylaxis recommended?

- How long are people infectious for?

- Are there infection preventative measures that could be recommended?

- Is the current rise in cases in children being investigated?

- What advice should I give to a parent who is concerned their child is seriously unwell?

What is group A streptococcus?

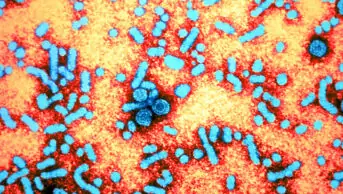

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) — also known as Streptococcus pyogenes — are Gram-positive bacteria, which commonly colonise the throat and skin. People may carry GAS on their skin and in the throat and not become ill[3].

What illnesses are caused by group A streptococcal infection?

GAS can cause throat infection, scarlet fever or skin infections (e.g. cellulitis or impetigo)[3].

Very rarely, it can cause severe illness, called invasive group A streptococcal disease (iGAS), where the bacteria enters other parts of the body (e.g. the lungs, blood or muscles). Invasive disease can be more common in people who are already ill, or who are undergoing treatment that affects the immune system (e.g. some cancer treatments)[3]. In children, the risk of iGAS/severe cases is also associated with chickenpox and influenza co-infection; currently, influenza rates are higher than in previous years[4,5].

Two of the most severe types of iGAS infection are necrotising fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome.

GAS has been investigated for its role in the development of post-streptococcal infection sequelae, including acute rheumatic fever, acute glomerulonephritis and reactive arthritis. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease are the most serious autoimmune sequelae of GAS infection[3].

How are group A streptococcus infections spread?

GAS is spread by close contact between individuals; through respiratory droplets and direct skin contact (e.g. with infected wounds or sores); through contaminated materials (e.g. towels and bedding); and by eating contaminated food[6].

What are the symptoms of infection?

Most often, infections and symptoms are mild, and include:

- Sore throat;

- Low grade fever;

- Minor skin infections (e.g. cellulitis and erysipelas)[7,8].

Patients, particularly children, may develop a condition called scarlet fever (see below).

Patients or the public reporting any of the above symptoms, after having had close contact with someone who has had iGAS within the past 30 days, should be advised to visit their GP or report to urgent care[6].

If fever alone is present and there are no other signs, symptoms or causes for concern, pharmacists can provide advice outlined in ‘Managing fever in children’.

Symptoms suggestive of iGAS include:

- High fever;

- Severe muscle aches;

- Localised muscle pain and tenderness;

- Unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. vomiting)[8].

Advice from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) states that patients or the public reporting any of the above symptoms should seek urgent medical help via A&E[7].

What is scarlet fever?

The initial clinical features of scarlet fever are non-specific and include sore throat, fever, headache, malaise, nausea and vomiting[9].

A characteristic diffuse, blanching rash usually develops by day two. It often starts on the upper trunk, before spreading to the rest of the trunk, the neck and limbs (see Photoguide A); the palms and soles are not affected.

On white skin, the rash looks pink or red, with the redness being particularly marked in the skin folds of the neck, arm pit, groin, elbow and knees (called Pastia’s lines). The rash has a ‘sandpaper’ feel, which may help detection in people with darker skin tones, who may not have as noticeable a colour change (see Photoguide B)[9].

Patients with scarlet fever have a flushed face, except for the area around the mouth; this is called circumoral pallor. This may be accompanied by exudative tonsillopharyngitis, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, small red spots on the palate (petechiae) and a ‘strawberry tongue’ (see Photoguide C)[9].

Patients initially have a ‘white strawberry tongue’, which has a white coating with red papillae visible beneath; when this coating is lost, the tongue appears beefy and red (‘red strawberry tongue’; see Photoguide D)[9].

Scarlet fever is highly contagious and, if not treated with antibiotics, can be infectious for two to three weeks after the onset of symptoms (with antibiotics, it remains infectious for 24 hours after starting treatment)[10].

More information on the clinical features of scarlet fever, including its diagnosis and management, can be found in ‘Scarlet fever: acute management and infection control’[9].

How is diagnosis confirmed?

The wide range of possible symptoms makes it difficult to identify and diagnose GAS infection early.

Laboratory tests can be used to differentiate between bacterial and viral pharyngitis, and a throat swab culture is recommended for the diagnosis of GAS pharyngitis. However, interpretation is made difficult as GAS are often present in the throat of young children without causing illness. Rapid streptococcal antigen tests are also available; these allow quick and easy access to results, but are less sensitive than culture[11].

Healthcare practitioners should notify their local health protection team of scarlet fever and iGAS cases and outbreaks, so that they can detect clusters and provide appropriate support and recommendations where necessary[1]. For example, if a patient is diagnosed with iGAS infection, it is sometimes necessary to check relatives or other close contacts by taking nose and throat swabs.

More on the management of close contacts of patients with iGAS can be found here.

Who is at increased risk of invasive group A streptococcal disease?

The following people are at increased risk of iGAS, should they be infected:

- Those who are in close contact with someone who has the disease;

- Those aged over 65 years;

- Those who have diabetes, cardiovascular disease or cancer;

- Those who have recently had chickenpox;

- Those who have concurrent influenza infection;

- Those who have HIV;

- Those who use some steroids or other intravenous drugs;

- Pregnant women or those who have recently given birth;

- Babies born to mothers infected with GAS[12].

What treatment is available?

Infections are usually treated with antibiotics. Penicillin is the treatment of choice, as GAS remains fully susceptible[8].

Adults aged 18 years and over should be prescribed penicillin V 500mg, four times per day or 1000mg twice daily for 5–10 days[13,14].

Children and young people under 18 years of age should be prescribed penicillin V first line, as detailed below.

Children and young people under 18 years of age should be prescribed penicillin V first line as follows:

- Aged 1–11 months: 62.5mg four times per day, alternatively 125mg twice daily for 5–10 days;

- Aged 1–5 years: 125mg four times per day, alternatively 250mg twice daily for 5–10 days;

- Aged 6–11 years: 250mg four times per day, alternatively 500mg twice daily for 5–10 days;

- Aged 12–17 years: 500mg four times per day, alternatively 1,000mg twice daily for 5–10 days [13,14].

As per the interim clinical guidance, developed by the NHS England Group A Streptococcus Clinical Reference Group and UKHSA Incident Management Team, and published on 9 December, healthcare professionals should be aware that “a five day course will be appropriate for many children, at the discretion of the treating clinician”. This guidance is valid until the end of January 2023 and will be reviewed with epidemiology of infections and emerging evidence.

Pharmacists should consult the British National Formulary or British National Formulary for Children for more detail on the contraindications, cautions, known drug interactions and potential adverse effects of penicillins. Clarithromycin, erythromycin (as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] guidance for sore throats) or azithromycin (as per UKHSA guidance for scarlet fever) may be used as alternatives where penicillin allergy or intolerance exists[4,14].

It should be noted that shortages of oral liquids of penicillins and macrolides have been reported[15].

In response to shortages, pharmacists will need to rationalise medicines according to their availability. It may be that cephalosporins and clindamycin are prescribed as shortages begin and patient-centred care (e.g. allergies, interactions and comorbidities) is taken into account.

Pharmacists may need to provide additional support to enable children to use solid dosage forms and may find this resource on their use, including manipulation, helpful.

Is the use of chemoprophylaxis recommended?

Guidance states that chemoprophylaxis may be offered to close contacts of iGAS patients.

Local health protection units (part of UKHSA) will monitor cases of iGAS at schools and make local decisions on whether chemoprophylaxis is needed. This usually requires two or more cases, based on risks. However, it should be noted that the evidence for its success is very limited, so each health prevention team would decide based on each individual scenario[4]

How long are people infectious for?

If left untreated, people with GAS infection are usually infectious for two to three weeks after developing a sore throat. If treated with antibiotics, people with GAS infection stop being infectious 24 hours after treatment is started[12].

As GAS infection is contagious, adult patients should avoid exposing other people by self-isolating until 24 hours after treatment begins and until they are well enough to return to normal activities. Children who have GAS infection should not go to school or day care during this period.

Are there infection preventative measures that could be recommended?

In the absence of any vaccine, good infection control is essential. People should be reminded to:

- Practice effective hand hygiene;

- Cover their faces when coughing and sneezing;

- Wear face coverings in crowded public places[7].

Close contacts and related households should also be advised that it may be necessary to take precautions, such as washing hands before preparing and eating food, and separating laundry to avoid cross-contamination and reduce the chances of infection[7].

Is the current rise in cases in children being investigated?

The UKHSA is investigating reports of an increase in lower respiratory tract GAS infections in children that has caused severe infection over recent weeks.

Cases of scarlet fever notification and consultations are higher than normal for this stage in the year and the rate of iGAS infection is currently higher than levels reported before the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 1)[1].

The increase in scarlet fever notifications also shows regional variation (see Table 2)[1].

There is currently no evidence that a new strain is circulating. The increase in cases is likely related to high amounts of circulating bacteria; however, there is a possible combination of contributory factors, including increased social mixing compared with previous years, as well as increases in other respiratory viruses[7].

What advice should I give to a parent who is concerned their child is seriously unwell?

It is important that healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, are aware of the signs and symptoms of mild and severe disease.

Parents should be advised to trust their judgement and seek advice if their child:

- Has symptoms that are getting worse;

- Is feeding or eating much less than normal;

- Has had a dry nappy for 12 hours or shows signs of dehydration (e.g. headache, tiredness, dry mouth, lips or eyes);

- Has a temperature of 38°C and is under three months old, or 39°C or higher and is older than three months;

- Is hotter than usual when touching the back or chest, or feels sweaty;

- Is very tired or irritable[7].

Parents should call 999 or go to A&E if:

- Their child is having difficulty breathing (e.g. making grunting noises or their tummy is sucking under their ribs)

- There are pauses when the child breathes;

- Their child’s skin, tongue or lips are blue;

- Their child is floppy and will not wake up or stay awake[7].

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Ryan Hamilton, consultant pharmacist — antimicrobials, Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and senior lecturer — pharmacy practice, De Montfort University, for expert review and editorial advice provided to support the production of this article.

- This article was updated on 19 December 2022 to correct the first-line penicillin V dosing information for infants aged 1–11 months

- 1Group A streptococcal infections: report on seasonal activity in England, 2022 to 2023. UK Health Security Agency. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/group-a-streptococcal-infections-activity-during-the-2022-to-2023-season/group-a-streptococcal-infections-report-on-seasonal-activity-in-england-2022-to-2023 (accessed Dec 2022).

- 2Mercer D, van der Merwe B. Strep A: Find out how many severe infections and scarlet fever cases are in your area. Sky News. 2022.https://news.sky.com/story/strep-a-find-out-how-many-severe-infections-and-scarlet-fever-cases-are-in-your-area-12762781 (accessed Dec 2022).

- 3Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of Group A Streptococcal Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:470–511. doi:10.1128/cmr.13.3.470

- 4Guidelines for the public health management of scarlet fever outbreaks in schools, nurseries and other childcare settings. UK Health Security Agency. 2022.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1110540/Guidelines_for_the_public_health_management_of_scarlet_fever_outbreaks.pdf (accessed Dec 2022).

- 5Weekly national Influenza and COVID-19 surveillance report Week 48 report (up to week 47 data) 1 December 2022. UK Health Security Agency. 2022.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1121698/Weekly_Flu_and_COVID-19_report_w48__1_.pdf (accessed Dec 2022).

- 6Group A streptococcal infections: guidance and data. UK Health Security Agency. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/group-a-streptococcal-infections-guidance-and-data (accessed Dec 2022).

- 7Group A Strep – What you need to know. UK Health Security Agency. 2022.https://ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2022/12/05/group-a-strep-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed Dec 2022).

- 8Stevens D, Bryant A. Severe Group A Streptococcal Infections. National Library of Medicine. 2016.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333425/ (accessed Dec 2022).

- 9Holden E, Ubhi H, Patel M. Scarlet fever: acute management and infection control. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/scarlet-fever-acute-management-and-infection-control (accessed Dec 2022).

- 10Scarlet fever. NHS. 2021.https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/scarlet-fever/#:~:text=You%20can%20spread%20scarlet%20fever,weeks%20after%20your%20symptoms%20start (accessed Dec 2022).

- 11Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;55:e86–102. doi:10.1093/cid/cis629

- 12Infection Prevention and Control Assurance Standard Operating Procedure 25 (IPC SOP 25) Alert Organisms – Group A Streptococcus (GAS) and Invasive Group A Streptococcus (iGAS). Black Country Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. 2019.https://www.bcpft.nhs.uk/documents/policies/i/1359-infection-prevention-and-control-assurance-sop-25-alert-organisms-invasive-group-a-streptococcus/file (accessed Dec 2022).

- 13Phenoxymethylpenicillin. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/phenoxymethylpenicillin/ (accessed Dec 2022).

- 14Choice of antibiotic. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84/chapter/Recommendations#choice-of-antibiotic (accessed Dec 2022).

- 15Wickware C. Children can be given oral solid dose antibiotics amid supply problems, NHS guidance says. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/children-can-be-given-oral-solid-dose-antibiotics-amid-supply-problems-nhs-guidance-says (accessed Dec 2022).