DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for over 30% of all global deaths1. In 2022, 39,000 people in England died prematurely of cardiovascular conditions, such as coronary heart disease and stroke in England2.

CVD refers to atherosclerosis (i.e. build-up of plaque) of arterial vessel walls, as well as thrombosis (i.e. formation of blood clots). CVD includes coronary artery disease, ischaemic stroke and peripheral arterial disease3. Non-modifiable risk factors include include age and male gender, while modifiable risk factors include hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, smoking, diet and physical activity.

CVD is a significant risk factor for morbidity and mortality, and adverse lipid profiles are a significant modifiable risk factor1.

In 2019, Mach et al. reported that some individuals have an increased personal risk of CVD owing to genetic factors. When optimising lipid profiles, it is important to actively manage other co-existing risk factors as part of a comprehensive clinical assessment (see Box 1)1,3. In 2023, Roeters van Lennep et al. highlighted that women experience changes in their lipid profile after the menopause, therefore elevated lipids should be treated early to reduce CVD risk4.

Box 1: National Institution for Health and Care Excellence recommendations to address modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease

- Discuss having a cardioprotective diet, such that total fat intake is ≤30% of total energy intake, saturated fats are ≤7% of total energy intake and where possible saturated fats are replaced by mono-unsaturated and polyunsaturated fats;

- Give advice on aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities;

- Consider weight management strategies;

- Give advice on how to minimise health risks related to alcohol;

- Signpost to smoking cessation services as appropriate;

- Review blood pressure and HbA1c and treat to target when clinically appropriate1.

Reducing the risk of a recurrent cardiovascular event in people with established CVD is referred to as secondary prevention3.

This article will provide an overview of how the updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance and new Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators relating to the secondary prevention of CVD can be applied in practice. It considers the context of the availability of newer drugs, such as alirocumab or evolocumab, to support pharmacists in how best to achieve these targets following an evidence-based approach.

Optimising lipid management

Despite around 7 million people in the UK having CVD, NICE suggests that many individuals are either not receiving lipid-lowering therapies or are on suboptimal treatment1. Owing to patient concerns around the side-effect profile of statins, including myalgia and digestive problems, there may be reluctance to initiate or continue with therapy5.

‘CVDPREVENT’ is a national primary care audit that uses GP data to assess the risk factors that may contribute to CVD6. These risk factors include atrial fibrillation, hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, non-diabetic hyperglycaemia and chronic kidney disease6. CVDP007CHOL is an indicator that looks at the percentage of adult patients with CVD, in whom the blood cholesterol was at target in the preceding 12 months. Data from June 2024, where treatment to target was non-HDL (high-density lipoproteins) <2.5mmol/L and LDL (low-density lipoprotein) <1.8mM/L, indicate that this was achieved for around 37% of adults in England6.

Raised total cholesterol (TC) and LDC-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels may increase the risk of CVD, in addition to other dyslipidaemias. The most common pattern is the atherogenic lipid triad where there is increased very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) remnants, increased LDL and reduced HDC-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels; however, there is a paucity of clinical evidence on how to interact with this triad. The accumulation of apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins, mainly LDL, is associated with atherogenesis. There is plaque progression as this invokes an inflammatory response7,8. Figure 1 shows how the atherogenic lipid triad confers CVD risk9.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

There are two new QOF indicators for general practice for 2024/202510. These indicators financially incentivise general practice to review patients on registers for coronary heart disease, stroke or transient ishaemic attack (TIA), peripheral arterial disease and chronic kidney disease to ensure that these patients are prescribed a statin or another lipid-lowering therapy (e.g. ezetimibe or inclisiran) where appropriate10.

For patients with CVD, who are on a register and have lipid levels that are out of range in the preceding 12 months, there is a target of achieving ≤2.6mmol/L non-HDL and ≤1.8mmol/L LDL cholesterol10. This aligns with the December 2023 update to NICE guidance that moved to absolute LDL targets for secondary prevention1. At the time, a cost-effectiveness analysis concluded that the previous lower ≤1.8 mmol/L target was not cost-effective, hence the more relaxed target of LDL ≤2.0 mmol/L1.

There is some debate around lipid targets for secondary prevention; for example, current guidance from the US National Cholesterol Education Program suggests LDL target levels of less than 1.8 mmol/L in very high-risk patients11. The European Society of Cardiology guidance reports that a reduction to 1.8mmol/L LDL — or at least a 50% reduction — is optimal, especially in those who are at increased risk of CVD3.

These targets may be difficult to achieve in general practice owing to the number of patients that this will be relevant to and the large size of chronic disease registers. This means that many more patient may need clinical review to address CVD risk factors. Moreover, it is important to consider the educational needs of clinicians and patients as well as workforce issues within primary care. Clinical pharmacists may support this work in general practice and there is a role for community pharmacy to support achieving treatment to target for hypertension, as well as providing education on lipid management to patients to support implementation of national guidance.

This education may relate to medication-related queries, as well as signposting patients to local services to support improving lifestyle factors, such as diet and exercise.

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

LDL-C may be used as an indicator for a response to lipid-lowering therapy. A reduction in LDL is associated with a reduced risk of occlusive vascular events3.

In 2010, the Cholesterol treatment trialists’ (CTT) collaboration — an international group of clinical experts and researchers — published its meta-analyses of individual participant data from 26 randomised trials involving at least 1,000 participants11. The CCT reviewed participants that had at least two years of more versus less intense treatment regimens with statins. Trials were included where the main effect of intervention was a reduction in LDL. It is known that a reduction in LDL is associated with a lower risk of occlusive vascular events, thus the safety of intensification of lipid-lowering therapy was assessed11.

Impressively, each 1.0mmol/L reduction in LDL reduced the rate of CVD events by just over 20%. Interestingly, this meta-analysis suggests further lowering may confer additional benefit. Research suggests that statin monotherapy would achieve this for most patients3.

Review of at-risk patients

People with CVD may be reviewed opportunistically, following hospital discharge or in the context of a planned review for a long-term condition, such as diabetes or cardiac disease. Community pharmacists could take the opportunity to perform medication reviews with at-risk patients. A blood pressure check as part of the ‘NHS community pharmacy hypertension case-finding advanced service’ may be performed as part of a local pathway by GP surgeries to support treatment to target initiatives12.

It is important to take a holistic review of patient needs when performing a CVD review. This may involve history taking with assessment of symptoms, physical examination and review of investigations.

A review would also encompass a medication review and optimisation of medication as clinically indicated. It is relevant to consider non-pharmacological approaches to CVD risk, which may address modifiable risk factors, as well as the patient perspective on their own health, ensuring that the review is individualised (see Box 1)1. This review may be delivered by multiple members of a multidisciplinary team in the community, including community and clinical pharmacists. These reviews should be personalised and may take place in a designated CVD clinic or opportunistically to facilitate access.

Baseline blood test results may be available in primary care; however, if there has been a CVD event and medications have been started in secondary care this may be challenging to access.

Available treatments for secondary prevention of CVD

Statins

Statins reduce cholesterol synthesis in the liver by competitively blocking the activity of HMG-CoA reductase. As hepatic cholesterol levels decrease, hepatocytes increase LDL receptor synthesis, thus there is more LDL uptake from the blood13.

In addition to a reduction in LDL, there is increasing recognition that earlier more intense therapy over a longer period of time is beneficial14.

NICE advocates the use of a high-intensity and high-potency statin, such as atorvastatin or rosuvastatin (see Box 2)1. A lower dose of statin may be considered when there are risk factors for muscle and liver toxicity, for example; in the frail or when there is a concern about renal function1. Additional information on available statins, initiation and considerations for interactions and adverse events can be found in ‘Assessment and prevention of cardiovascular disease‘.

Box 2: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations for the use of high-intensity statins

- Atorvastatin 20–80mg or rosuvastatin 10–40mg can be prescribed to patients that require high-intensity statins;

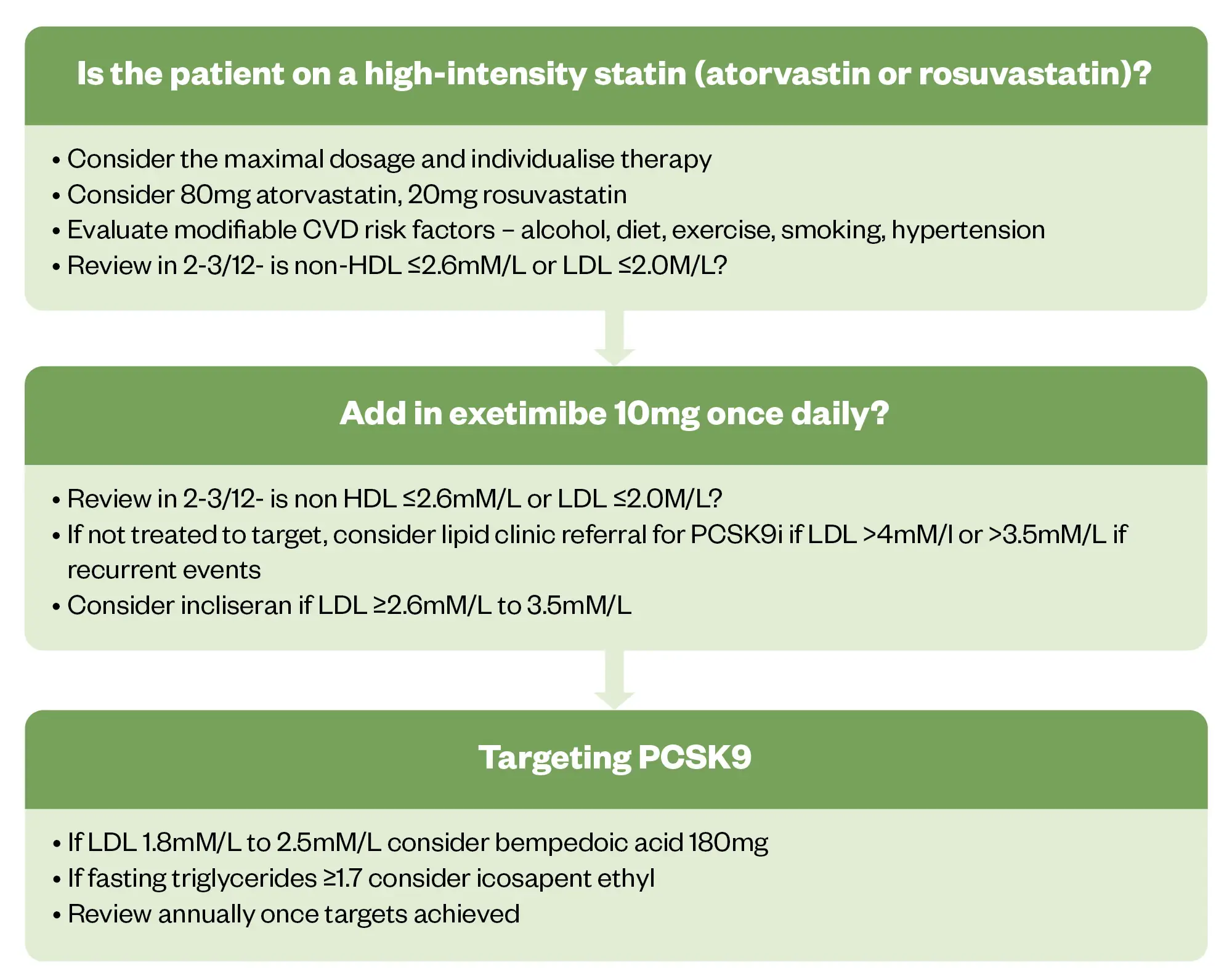

- Lipid-lowering therapy may be intensified when reviewing LDL targets or approximate reductions in LDL (see Figure 2);

- Acute coronary syndrome should not delay statin therapy;

- Long-term trials with atorvastatin 80mg have shown higher rates of elevated liver transaminases and risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis comparable to those risks seen at lower-dose statins. ALT for statins should be checked at baseline, two to three months after initiation (or any dose increase) and again at one year. If satisfactory, ongoing repeat testing is not required. If there is a concern about elevated liver transaminases, dose reduction of statins may be considered1,9.

The maximal tolerated dose of statin should be used as this will confer CVD risk reduction. The NHS Accelerated Access Collaborative (AAC) — a partnership between the patient groups, government bodies, industry and NHS bodies that aims to streamline the adoption of new innovations in healthcare — recommends that high-intensity statins should achieve LDL of less than ≤2.0mmol/L9. Around one-third of patients achieve this target one year after a presentation of acute coronary syndrome15. In 2018, Gencer and Mach reported that the reasons for more patients not achieving target may be related to lack of treatment intensification, concern about side effects and patients stopping their own therapy16.

The NHS AAC report, published in 2020, stated that low- or medium-intensity statins may be used in cases of drug intolerance or interactions9. Adherence to treatment and any patient concerned should be addressed at each contact in primary care; this includes both at the GP surgery and in community pharmacy9.

Ezetimibe + statin

Ezetimibe inhibits intestinal uptake of dietary and biliary cholesterol. As there is less cholesterol circulated to the liver, the liver increases LDL receptor expression, which means that more LDL is taken up from the blood16.

Ezetimibe may be considered in patients that do not achieve a LDL ≤2.0mmol/L with their current lipid-lowering treatment. This means that ezetimibe may be used in combination with the maximum tolerated dose of statin16. Ezetimibe may also be used in those that are unable to tolerate statin therapy and is prescribed as a 10mg, once-daily dose9.

Given the mechanism of action of ezetimibe, gastrointestinal side effects — such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and flatulence — may occur. Myalgia is thought to occur commonly16.

A reduction in first and total CVD events has been demonstrated with intensification of lipid-lowering therapies when compared with less aggressive LDL-lowering strategies with statins alone. The ‘IMPROVE-IT’ trial, results of which were published in 2016, showed that adding ezetimibe to simvastatin further reduced LDL by 24% and lowered the risk of first cardiovascular events (n=18,144). A reduction in first and total events was also demonstrated17.

NICE has stated that combination therapy with a statin and ezetimibe is likely to give greater reduction in non-HDL-C or LDL-C when compared with doubling the dose of the statin1.

In 2018, Zhan et al. demonstrated that ezetimibe has modest beneficial effects on the risk of CVD endpoints with a reduction in non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) and non-fatal stroke, this is thought to be related to the reduction in LDL and triglycerides18.

Approximate reductions in LDL-C that can be achieved with different intensities of statins and ezetimibe can be seen in Table 19.

PCSK9 inhibitors

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is a protein that binds to LDL receptors on hepatocytes causing their breakdown in lysosomes. This means that inhibiting this protein prevents the breakdown of LDL receptors allowing increased clearance of LDL from the blood19.

The following PCSK9 inhibitors should be considered to achieve treatment to target if statins and/or ezetimibe have been ineffective. This may owe to drug intolerances or maximal tolerated therapy not achieving NICE targets.

Inclisiran

Inclisiran is a small interfering RNA drug, targeting PCSK9 gene expression. It does this by degrading mRNA such that LDL receptors are not degraded. In 2021, inclisiran was approved by NICE for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia or mixed dyslipidaemia, as well as for high-risk CVD patients or people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia who need further lowering of LDL-C levels20. A single dose can reduce LDL by 50% for up to six months, with a low risk of adverse side effects. The reduced frequency of administration may improve patient adherence19,21.

Inclisiran is available as a 284mg solution for subcutaneous injection in a pre-filled syringe. After initial dosing, the injection is repeated at three months, then at six months thereafter20. No dose adjustments are required in older people or in people with hepatic or renal impairment. Caution is advised in the case of severe kidney disease. Although injection site reactions have been reported, it is unlikely to interact with other medicines because it does not have any effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes20.

NICE has stated that there are no long-term data on the reduction of CVD events with inclisiran, and there has been controversy owing to concerns that long-term data on CVD outcomes and safety were not available at the time of approval22. Novartis, its manufacturer, has a commercial arrangement with the NHS to provide the drug at a discount23.

Inclisiran can be given in primary care, which contrasts with other injectables, which are given in secondary care. However, the British Medical Association has expressed concern that the capacity to undertake this work in primary care had not been considered24.

Alirocumab and evolocumab

Alirocumab (Praluent; Sanofi) and evolocumab (Repatha; Amgen) are monoclonal antibody treatments that bind to PCSK9 and therefore prevent PCSK9 binding to LDL receptors. This means that that LDL receptors are not broken down and can bind LDL in the blood25,26. These treatments are only offered to people with higher levels of LDL. NICE advised that many patients eligible for these treatments do not receive them, this may be owing to lack of referral to specialist lipid services. These drugs have been shown to reduce CVD events with LDL reduction. According to NICE, there are no data directly comparing inclisiran with alirocumab or evolocumab20.

The NICE eligibility criteria for initiation of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy by condition and CVD risk can be seen in Table 29.

Alirocumab is a pre-filled 150mg subcutaneous injection, administered every two to four weeks. NICE guidance is based on research that shows there is a reduction of LDL of nearly 48% and reduced CVD mortality when compared with control25. Initially, 75mg is administered every two weeks and, depending on the reduction of LDL-C required, dosing may be increased to 150mg every two weeks or 300mg every four weeks25. No dose adjustments are required in older people or in people with hepatic or renal impairment. Although injection site reactions have been reported, other possible side effects include upper respiratory symptoms and itching25.

Evolocumab, which is administered by subcutaneous injection every two to four weeks, has been shown to reduce LDL-C by 60–70% compared with control26. This is delivered by a using a pre-filled pen containing 140mg evolocumab.

Evolocumab may be given every two weeks or as a 420mg dose four-weekly for established CVD26. No dose adjustments are required in older people or in patients with hepatic or renal impairment. Although injection site reactions have been reported, other possible side effects include nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory symptoms and back pain26.

Other lipid-lowering therapies

Bempedoic acid inhibits ATP-citrate lyase upstream of HMG-CoA-reductase, thus reducing LDL level27. NICE has recommended combination treatment with bempedoic acid + ezetimibe where statins are contraindicated or not tolerated, and ezetimibe monotherapy does not result in treatment to target28. When combined with ezetimibe, bempedoic acid produces an additional LDL-C reduction of around 28%28. Bempedoic acid may be associated with an increased risk of gout, anaemia and myalgia.

There are no data directly comparing bempedoic acid with ezetimibe with either alirocumab or evolocumab.

Icosapent ethyl is a highly purified formulation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) found in fish oil29. Previously fish oils also contained docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). It was demonstrated that DHA may cause an increase in LDL, this contrasts with EPA. Icosapent ethyl is indicated in those that are already on statins with triglycerides greater than 1.7mmol/L, in the context of CVD30.

Patient monitoring requirements

The following lipid-lowering therapy pathway is proposed as part of an annual review for patients. The diagram below shows when patients should be monitored and when treatment intensification should be considered (see Figure 2)1,9.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Adherence to medication is a significant problem in secondary prevention, when initiating and reviewing patient’s medication, pharmacists should ensure medication is being taken as directed, check the patient understanding of mechanism of action and the risks and benefits of the medication, and ask about side effects to address any reasons for non-adherence to a lipid-lowering regimen.

Additional information on adverse effects and intolerance to lipid-lowering therapies can be found here.

Case study

The following case study demonstrates how the above pathway can be used in primary care.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old male with a history of non-ST elevation MI and stent placement was seen at the GP surgery for a cardiac review.

His blood tests showed lipids above target with non-HDL 3.2 mM/L and LDL2.4mM/L.

Modifiable CVD risk factors were assessed; his blood pressure was well controlled, he was an ex-smoker since his MI and he reported a good diet on further questioning. He had recently joined a swimming club.

His previous medication history was reviewed and it was noted that he had previous prescriptions of statins and ezetimibe. He had tried simvastatin 20mg and atorvastatin 80mg but experienced aches and pains. He declined a lower dose of atorvastatin and did not want to try low-dose rosuvastatin owing to the possibility of side effects. His current medication list included ezetimibe on his repeat prescriptions, but he explained that he had stopped this owing to side effects.

He agreed to reintroduce the medication to see if the side effects reoccurred. Unfortunately, he reported side effects of joint pains returned, which resulted in discontinuation. Baseline bloods showed a raised serum urate; therefore, bempedoic acid was not used.

The patient was in agreement to try inclisiran and was counselled on its mechanism of action, side effects, frequency of administration and the blood test monitoring required. Furthermore, he was advised that while there is no CVD outcome data and that inclisiran is a ‘black triangle’ medication — which means that it is subject to intensive monitoring and that adverse reactions should be reported31 — there is evidence of significant decreases in LDL19,21.

His repeat blood tests showed lipids below target with non-HDL 2.2 mM/L and LDL1.0mM/L. Given that his lipid profile is at target, future monitoring would include an annual CVD review, which would include relevant monitoring blood tests.

Additional considerations

In recent years, there have been challenges with obtaining some lipid-lowering therapies owing to interruptions in supply. For example, there have been supply issues with the 80mg formulation of atorvastatin, meaning that 40mg formulations have been prescribed instead32. Similarly, there have been intermittent supply issues with ezetimibe with patients trying to source this from alternative local pharmacies with varying levels of success33. This may mean that patients inadvertently stop their medication, which may result in some not restarting medication unless prompted by a healthcare professional.

Community pharmacists may reinforce education on medication and the importance of continuation, they may source alternative doses of a drug that may be available and advise patients on supply issues.

Additional information on advising patients on medicine shortages can be found in ‘How to navigate and ensure effective patient communication about medicines shortages’.

Conclusions

LDL-C may be used as an indicator for a response to lipid-lowering therapy. A reduction in LDL is associated with a reduced risk of occlusive vascular events. It is advised that early and optimal intervention yields the greatest benefit, this is particularly evident in high-risk individuals. Importantly, all guidance refers to an individualised approach to risk management that includes lifestyle factors.

The maximal tolerated dose of statin will confer CVD risk reduction. Moreover, ezetimibe used in combination with a statin can further reduce LDL. Furthermore, targeting PCSK9 can result in a significant reduction in LDL.

Comprehensive, proactive clinical assessment allows for evaluation of risk factors associated with CVD. The majority of patients in primary care will have stable disease that will require support for risk factor modification, including intensification of treatment to achieve lipid targets.

- 1.Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238

- 2.Cardiovascular disease and diabetes profiles: statistical commentary. UK Government: Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/cardiovascular-disease-and-diabetes-profiles-march-2024-update/cardiovascular-disease-and-diabetes-profiles-statistical-commentary

- 3.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal. 2019;41(1):111-188. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- 4.Roeters van Lennep JE, Tokgözoğlu LS, Badimon L, et al. Women, lipids, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a call to action from the European Atherosclerosis Society. European Heart Journal. 2023;44(39):4157-4173. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad472

- 5.Hobbs FR, Banach M, Mikhailidis DP, Malhotra A, Capewell S. Is statin-modified reduction in lipids the most important preventive therapy for cardiovascular disease? A pro/con debate. BMC Med. 2016;14(1). doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0550-5

- 6.CVD Prevent: Data & Improvement Tool. CVD Prevent. Accessed September 2024. https://data.cvdprevent.nhs.uk/home

- 7.Nomikos T, Panagiotakos D, et al. Hierarchical modelling of blood lipids’ profile and 10-year (2002–2012) all cause mortality and incidence of cardiovascular disease: the ATTICA study. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14(1). doi:10.1186/s12944-015-0101-7

- 8.Tokgözoğlu L, Libby P. The dawn of a new era of targeted lipid-lowering therapies. European Heart Journal. 2022;43(34):3198-3208. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab841

- 9.Summary of National Guidance for Lipid Management for Primary and Secondary Prevention of CVD. NHS Accelerated Access Collaborative. 2020. Accessed September 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/aac/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2020/04/lipid-management-pathway-v7.pdf

- 10.Quality and outcomes framework guidance for 2023/24. NHS England. 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/quality-and-outcomes-framework-guidance-for-2023-24/

- 11.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials. The Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61350-5

- 12.NHS Community Pharmacy Blood Pressure Check Service. NHS England. Accessed September 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/pharmacy-services/nhs-community-pharmacy-blood-pressure-check-service/

- 13.Davidson MH, Robinson JG. Safety of Aggressive Lipid Management. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(17):1753-1762. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.067

- 14.Abdul-Rahman T, Bukhari SMA, Herrera EC, et al. Lipid Lowering Therapy: An Era Beyond Statins. Current Problems in Cardiology. 2022;47(12):101342. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101342

- 15.Friday KE. Aggressive Lipid Management for Cardiovascular Prevention: Evidence from Clinical Trials. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2003;228(7):769-778. doi:10.1177/15353702-0322807-01

- 16.Gencer B, Mach F. Lipid management in ACS: Should we go lower faster? Atherosclerosis. 2018;275:368-375. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.06.871

- 17.Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, et al. Reduction in Total Cardiovascular Events With Ezetimibe/Simvastatin Post-Acute Coronary Syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;67(4):353-361. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.077

- 18.Zhan S, Tang M, Liu F, Xia P, Shu M, Wu X. Ezetimibe for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality events. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018(11). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012502.pub2

- 19.Zhang Y, Chen H, Hong L, et al. Inclisiran: a new generation of lipid-lowering siRNA therapeutic. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1260921

- 20.Inclisiran for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta733

- 21.Scicchitano P, Milo M, Mallamaci R, et al. Inclisiran in lipid management: A Literature overview and future perspectives. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2021;143:112227. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112227

- 22.Inclisiran: the “extremely unusual” political influence behind the novel drug’s approval. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2023. doi:10.1211/pj.2023.1.204848

- 23.Iacobucci G. GP leaders advise practices not to prescribe cholesterol lowering drug inclisiran. BMJ. Published online August 1, 2023:p1757. doi:10.1136/bmj.p1757

- 24.RCGP and BMA update: Information on the proposals for the prescription of inclisiran in primary care settings. Royal College of General Practitioners. 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/representing-you/policy-areas/inclisiran-position-statement

- 25.Alirocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016. Accessed September 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta393

- 26.Evolocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016. Accessed September 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta394

- 27.Banach M, Penson PE, Farnier M, et al. Bempedoic acid in the management of lipid disorders and cardiovascular risk. 2023 position paper of the International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2023;79:2-11. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2023.03.001

- 28.Bempedoic acid with ezetimibe for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. Accessed September 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta694

- 29.Jia X, Koh S, Al Rifai M, Blumenthal RS, Virani SS. <p>Spotlight on Icosapent Ethyl for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction: Evidence to Date</p> VHRM. 2020;Volume 16:1-10. doi:10.2147/vhrm.s210149

- 30.Icosapent ethyl with statin therapy for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in people with raised triglycerides. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta805

- 31.Black Triangle (▼) medicines part of an EU-wide scheme. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2014. Accessed September 2024. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/black-triangle-medicines-part-of-an-eu-wide-scheme

- 32.Negotiators warn statin shortage is having “serious impact” on pharmacies as price spikes. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2023. doi:10.1211/pj.2023.1.190757

- 33.Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Formulary. NHS. January 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://www.cambridgeshireandpeterboroughformulary.nhs.uk/chaptersSubDetails.asp?FormularySectionID=2&SubSectionRef=02.12&SubSectionID=C100#240