Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

By the end of this article, you will have a better understanding of:

- The availability of different models that support effective, well-structured communication during a consultation;

- The importance of active listening and non-verbal cues;

- Ways in which prescribers can continuously improve their communication skills.

RPS Competency Framework For All Prescribers

This article aims to support the development of knowledge and skills related to the following compentencies:

Domain 1: Assess the patient (1.3, 1.4, 1.5)

- Introduces self and prescribing role to the patient/carer and confirms patient/carer identity;

- Assesses the communication needs of the patient/carer and adapts consultation appropriately;

- Demonstrates good consultation skills and builds rapport with the patient/carer.

Domain 3: Present options and reach a shared decision (3.2, 3.3, 3.6)

- Explains the material risks and benefits, and rationale behind management options in a way the patient/carer understands, so that they can make an informed choice;

- Explores the patient’s/carer’s understanding of a consultation and aims for a satisfactory outcome for the patient/carer and prescriber.

Domain 5: Provide information (5.1, 5.2)

- Assesses health literacy of the patient/carer and adapts appropriately to provide clear, understandable and accessible information;

- Checks the patient’s/carer’s understanding of the discussions had, actions needed and their commitment to the management plan.

Introduction

The ability to communicate is an essential skill embedded in code of conduct for all healthcare professionals[1–4]. Millions of conversations are held with patients each day; in 2021/2022, there were an estimated 570 million patient interactions, equating to 1.6 million daily contacts, within UK general practice, community, hospital, mental health and ambulance services[5]. It is essential that clinicians actively listen and ask effective questions to work in a manner that allows patients to be empowered and have control over their health and wellbeing[6–8].

Domain 1 of the ‘RPS Competency Framework for All Prescribers’ specifies that clinicians should demonstrate good consultation skills and build rapport with the patient/carer[9]. Good consultation skills include actively listening, using positive body language, asking open questions, remaining non-judgmental, and exploring the patient’s/carer’s ideas, concerns and expectations[9]. A central tenet of modern consultation models, such as the Calgary-Cambridge model, is the building of rapport and it is highlighted that effective communication is essential for quality care, patient satisfaction, recall, understanding, concordance and successful outcomes[10,11]. Building a good rapport also develops trust between the clinician and patient, which can lead to improved information sharing and better differential diagnosis formation[12–15]. Communication turns theory into practice and how we communicate is just as important as what we say[10].

This article will explore the importance of communication skills in prescribing consultations, the types of communication that prescribers can use in day-to-day practice with links to several consultation models and how to use them to develop positive consultation outcomes.

It is recommended that you read this article in conjunction with these resources from The Pharmaceutical Journal:

- ‘Principles of person-centred care for prescribing’;

- ‘Factors influencing effective communication when prescribing’;

- ‘How to build and maintain trust with patients’;

- ‘How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting’.

To help further expand your prescribing skills, additional related articles are linked throughout. You will also be able to test your knowledge by completing a short quiz at the end of the article.

Access the prescribing advice and support from the RPS here or click on the images below.

Whether you’re interested in becoming a prescriber, need advice on how to find a designated prescribing practitioner, or are currently working as a prescriber and looking to expand your scope of practice, the RPS has produced a range of resources to help you practice safely and confidently.

Using communication skills to enable person-centred care

Good communication skills are more than just talking with a patient: they are about connecting. There should be an acknowledgement of the lived experience of the person (personhood), their knowledge and patient expertise (experiential knowledge gained from personally managing the day-to-day experience of illness). Communication skills should be used to identify and recognise what is important to the person and identify what the patient thinks is happening to them. Not doing so can lead to interactions breaking down or create a consultation of two realities: that of the patient and that of the prescriber.

For example, if a patient presents with an undiagnosed skin condition, the prescriber may be able to quickly recognise symptoms and form a generalised view of the patient: “Mrs. Jones, I think you have tinea corporis (dermatophytosis).” Meanwhile, the patient may be sitting there having unsuccessfully tried a number of over-the-counter emollients and is convinced they have cancerous growth. A good patient-centred consultation should meet both the clinician’s and patient’s needs. The specific views of reality, disease and illness should be addressed from both contexts[16].

Reflection in practice: patient expertise

Listen to this extract from The PJ Pod where Lelly Oboh, consultant pharmacist, care of older people at Guys and St Thomas’ NHS Community Health Services, talks about the importance of patient expertise. As you listen, consider how patient experience and their unique insights can be used to improve effective communication during a consultation.

The full podcast episode is available here.

The value of communication models

While forming connections and establishing rapport should be viewed as a natural process, a range of different models, frameworks and tools have been developed that help prescribers to structure their consultations. Early consultation models introduced the importance of establishing the patient’s ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE)[17–19]. The concept of ICE has been further developed within the UK by the Personalised Care Institute and National Voices, and is advocated by the ‘NHS long-term plan’[20].

Focus in practice: the ICE consultation model

Ideas: This relates to the patient perspective, the beliefs they hold about their health and their understanding of their condition. It is an opportunity to explore the prescriber and patient’s respective views of reality, disease and illness.

Example:

Prescriber: “What do you think may be causing your symptoms?”.

Patient: “I read online that this lesion could be linked to cancer, it has developed so quickly”

Concerns: It is important to understand what matters most to the patient. This could be related to their concerns about the condition itself or the holistic impact that symptoms or treatment might have on their life.

Example:

Prescriber: “Is there anything you are especially worried about?”

Patient: “If I have to go into hospital or become ill with this, who will look after my disabled husband?”

Expectations: Understanding the patient’s expectations is necessary to ensure the realities of the patient and prescriber remain aligned and to avoid a dysfunctional consultation where the prescriber and patient’s needs are not addressed.

Example:

Prescriber: “What outcomes were you hoping for in our consultation today?”

Patient: “Well, I am hoping I am going to get a referral to a dermatologist.”

Having established what the patient expects you can respond accordingly, outlining the possible options and reaching a shared decision about the treatment plan.

In addition to ICE, a number of other consultation models have been identified. One of most commonly used is the Calgary-Cambridge model[10]. The model provides a structured guide to the consultation process and has five steps:

- Initiating the session;

- Gathering information;

- Physical examination;

- Explanation;

- Planning.

The model is supported by two pillars: providing structure and building a relationship. Each stage of the model relies on effective communication. For instance, gathering information requires the prescriber to ask questions that consider the biomedical perspective as well as the background, context and individual circumstances of the patient. Building the relationship similarly requires use of appropriate non-verbal behaviours, developing rapport and involving the patient throughout.

Core communication skills

Successful use of communication skills and models has been shown to improve consultation outcomes and clinician job satisfaction and improving communication skills should be viewed as an area of long-term professional development[21]. Prescribers should reflect on their interpersonal effectiveness no matter how long they have been in practice and look to continuously expand their skillset. Shifts in the nature of healthcare amplify the need for even experienced prescribers to continually enhance their communication skills and knowledge[10]. Initially, it is important to master the fundamental components of good communication, many of which can be quickly integrated into prescribing practice.

Open-ended and closed questions

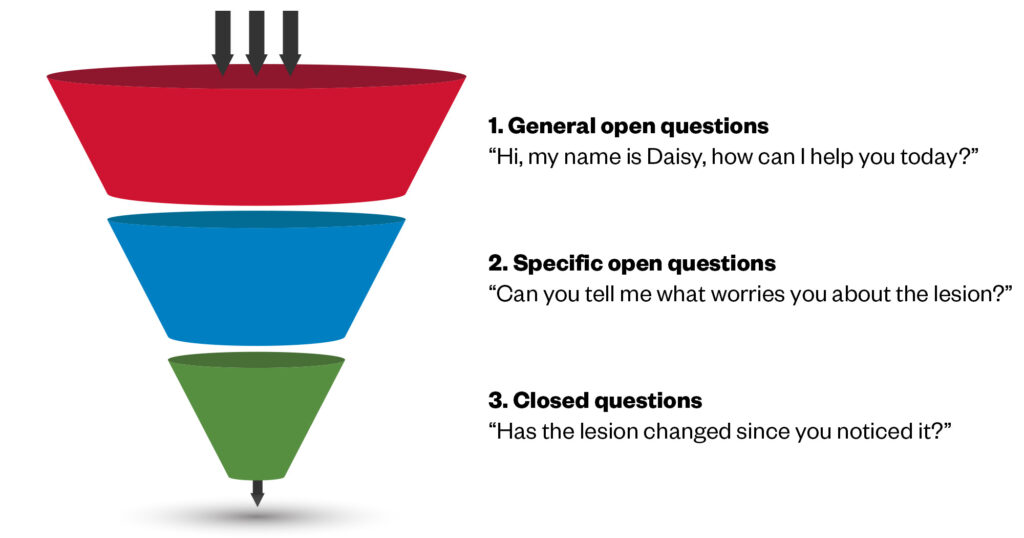

Open questions are powerful consultation tools: they give the patient an opportunity to tell their story. Open questions are sometimes described as the ‘five why’s — who, what, when, where and why. An effective way to start the consultation following an introduction can simply be asking “how can I help you today?” and then allow the patient an opportunity to talk without interruptions. Asking broad, open questions may feel daunting initially because you have no way to know what the patient may say in response; however, it also allows for highly effective information gathering which will enhance the overall efficiency of the consultation.

It is important to give consultations sufficient time and to not feel compelled to fill silences. When asking the patient to tell their story, leaving a gap before asking your next question can encourage patients to keep talking and may lead to valuable additional information being volunteered. This is particularly true for issues that are sensitive in nature. A short silence can demonstrate to the patient that you are actively listening and present, allowing them the time they need to articulate something that may be difficult for them to share. This can create trust and allow the patient to be open and provide more details.

Reflection in practice

A 2002 study revealed that the mean duration of open speech by patients in an out-patient clinic was 92 seconds and the median was just 59 seconds; only 2% continued for more than 5 minutes. For context, 90 seconds is roughly the same amount of time as washing your hands twice[22].

Think about a recent patient consultation. Would 90 seconds have been long enough to gather sufficient information to inform your approach to the rest of the consultation?

After allowing time for patients to tell their story, the prescriber can then move to more specific questions through the consultation (see Figure) to build a complete timeline and picture of the presenting complaint[10,23]. Closed questions allow more specific questions to be asked such as “When did the pain start?”. Avoid leading questions such as “You don’t miss any doses of your medication, do you?” and resist the temptation to direct the patient’s answers.

Shutterstock.com/The Pharmaceutical Journal

It is important to acknowledge that patient interactions can be complex and that organic dialogue between patients and healthcare practitioners does not always follow a clear pattern of open and closed questions. The setting and environmental context can also affect the prescriber’s ability to structure questions effectively. In 2022, Collins et al. examined how hospital emergency department doctors present questions to patients and defined them as ‘utterances’, intended to explicitly ask for information that elicit the kinds of details that are relied upon within their setting of practice[23]. They highlighted some of the real-life barriers and influences that can prevent patient-focused consultations from developing. These included the lack of patients’ negotiating powers when it came to the selection of questions asked and the terms of reference for the conversation. These influences may result both from the overuse of closed questions that fail to identify the full extent of the patient’s needs and closed questions which fail to elicit direct answers.

Non-verbal communication

In some interactions, non-verbal cues — e.g. sounds such as tuts, ‘umms’, ‘ahhs’ and sighs — and body language can contribute up to 90% of communication exchanged. These cues work in both directions: they can tell you a great deal about what the patient may be thinking or experiencing and also allows prescribers to convey a supportive and empathetic demeanor and attitude. It is important to be aware of cultural characteristics when considering verbal and non-verbal communication: lack of awareness and failure to account for these differences has been shown to lead to poor care, and misdiagnosis[24].

The prescriber should learn to regularly assess non-verbal cues. Is the patient not maintaining eye contact, are they distracted? How did they react to what you just said? Are they rolling their eyes? What does their facial expressions or posture relay to you? Note that for virtual consultations these non-verbal cues will manifest differently and accommodation should be made. For more on this topic, see ‘Remote consultations: how pharmacy teams can practice them successfully’.

Active listening

Prescribers can use active listening to develop a positive and constructive relationship with the patient. It is more than simply conveying positive body language; it requires intentionally focusing on what the person is saying and demonstrating that you are present. Active listening has been shown to improve trust[25]. NHS Improvement’s report ‘Spoken communication and patient safety in the NHS’, published in 2018, looked at six key areas:

- The communication environment;

- Information exchange;

- Attitude and listening;

- Aligning and responding;

- Creating the preconditions for effective communication within a team;

- Communicating with specific groups[25].

The report stated that “effective communication is associated with respect, commitment, positive regard, empathy, trust, receptivity, honesty and an ongoing and collaborative focus on care”.

“People are better listeners in situations where there is adequate time, privacy and comfort, and when clinicians sound committed to the patient’s care and are emotionally attuned to the needs of patients, carers and staff,” it added[25].

Models have been identified that help the clinician to be present to the patient, these include Egan’s ‘SOLER’ model, which stands for ‘sit squarely’, with an ‘open posture’, ‘leaning slightly forward’, ‘eye contact’ and ‘relax’[26]. This approach was further developed by Stickley, who proposed the ‘SURETY’ model (which stands for ‘sit at an angle’, with ‘uncrossed legs and arms’, ‘relax’, ‘eye contact’, ‘touch’ and ‘your intuition’[27]. Some healthcare professionals report feeling less confident about the inclusion of touch within this model however therapeutic touch can be considered if it is appropriate to the situation and can benefit communication. Touch may be procedural as part of a clinical task or expressive contact which is not related to the task[28]. Clinicians should be sensitive to cultural differences and previous traumatic life experiences. The inclusion of intuition in the ‘SURETY’ model is also significant. Intuition is part of the process of clinical reasoning and it guides how the prescriber will employ the other components of the model[29]. For example, your intuition may guide how you employ eye contact and whether use of touch is appropriate to the situation.

It is important to be aware of real-world influences, which can present barriers to employing person-centred communication models. Many prescribers face significant workload and time pressures leading to practices such as typing up notes real-time during consultations. While this may be a helpful strategy for the prescriber it can be distracting to the patient and reduces the capacity to pick up on non-verbal cues or encourage the patient to share more details about their condition, symptoms and concerns. If note taking is to be done during the consultation, this should be contracted with the patient at the start. The patient should be asked: “Is it OK that I make notes while we talk? I do not want to miss anything and it helps me to process the information you share with me.” The clinician should ensure that they do not then turn their back on the patient and should remain aware of their body language and facial expressions.

For more information on effective documentation see the article ‘Writing patient notes: a guide for pharmacists’.

Reflecting back

Repeating a patient’s words back to them is a useful skill that can be employed during consultations. It is multifunctional: reflecting back can be used to summarise and repeat the patient’s story to them succinctly, helping them to organise their thoughts while also demonstrating that you have been actively listening and building trust.

Reflecting back also serves the functional purpose of checking that you have the correct information and have not missed anything important. It can also assist with clinical reasoning, speaking out loud and repeating the history of the presenting complaint supports ‘reflection in action’ and encourages ‘metacognition’ (i.e. thinking about thinking). This could take the form of asking yourself questions such as ‘is there anything I have missed? What else could this be?’.

Reflecting back is also useful if you suspect the patient has not understood information or an explanation given. In this situation, you can ask the patient to also reflect back to the clinician although judgement will be required to do this in a way that does not make the patient feel awkward or patronised. This could be achieved through a good opening to your sentence, such as: “I’m conscious that was quite a lot of information to take in. Just to check I have done a good job explaining it to you, can you summarise in your own words what we just discussed?”

Reacting to challenging conversations

As a prescriber there will be instances where communication with patients becomes difficult or overtaken by negative emotions (e.g. anger, fear, mistrust). While this should be rare, it is important to react constructively and view communication failures as an opportunity for learning. Reflection can be undertaken, perhaps with a mentor or colleague, to identify where your communication skills can be further developed or to identify improvement opportunities. This applies equally to all healthcare professionals regardless of how long they have been practising.

For more on this topic, see ‘Approaching difficult situations: how to have challenging conversations’.

Common reasons for dysfunctional consultations include:

- Failure to identify the true presenting complaint;

- Having two realities in the consultation — that of the clinician and that of the patient.

- Not being adequately ‘present’ to the patient which may negatively affect information sharing;

- When the clinician wants to avoid an area of discussion (e.g. where the prescriber may prefer to focus on the treatment or medicine rather than the needs of the patient or the topic is uncomfortable due to their own person experiences/lived experience)[30,31].

Improving your communication skills

Experiential learning methods incorporating observation, feedback and rehearsal can support the ongoing development of the prescriber’s communication skillset. The following approaches provide examples of ways this can be incorporated into your prescribing practice:

- Record a mock consultation and review this back individually or with peers or mentors. Being able to observe yourself in this way can highlight your use of non-verbal communication, try out new techniques and analyse your use of open and closed questions in a safe and supported environment;

- Patient feedback can be acquired in many ways (e.g. Friends and Family Test data; regularly acquired local data in your clinical area). When undertaking audits, patients’ feedback on communication competence should also be incorporated and gathered;

- Using 360 appraisals, where feedback is requested from a wide range of sources across the team, usually chosen by the reviewer. The 360 review is used as a learning and development aid and its main benefit is that it gives individuals better information about their experience, skills, behaviour, performance, and working relationships than more traditional appraisals, which tend to based on the line manager’s assessment alone. Patient feedback can also be incorporated into the review;

- A balint group is a group of clinicians who meet regularly and present cases to each other to discuss. The focus is on the emotions of the clinician and patient arising within the consultation, rather than the clinical content of the case;

- Building your emotional intelligence and awareness of your own personality: interrogating your own beliefs and behaviours and considering how this may affect communication with patients will also allow your communication skills to develop. It can also help us understand why we find particular patients difficult, and why consultations may have gone wrong;

- Tools such as the ‘Myers–Briggs Type Indicator’ and the ‘Honey and Mumford Learning Styles’ can be used to help understand differences between individuals and how best to communicate with them[32]. Prescribers can explore their own personal styles and communication preferences and discuss the results with a colleague, mentor, peer or supervisor;

- Critical reflection is an evidenced-based approach designed to engage higher and more challenging levels of thought that initiate transformative learning by connecting old to new knowledge[33]. It can be applied to the context of communication and interpersonal effectiveness and used as a tool to drive improvment.

Questions for reflection

- Reflect on a recent prescribing consultation that went really well. Did you get positive feedback from the patient? How was this demonstrated? What communication skills contributed to the positive experience?

- How do you think you can incorporate ideas, concerns and expectations into your everyday prescribing consultations? Have you tried this out in practice? Did you try asking the patient what is important to them?

- Reflect on one of your prescribing consultations where you may have experienced a challenge. Why do you think the challenges occurred? Were the specific views of reality, disease and illness addressed from both the patient and prescriber perspective?

- How do you build rapport within your consultations? We know that effective communication is essential for quality care, patient satisfaction, recall, understanding, concordance and outcomes. Reflect on your verbal and nonverbal skills, is there anything you need develop? What process might you try to do this?

Knowledge check

Expanding your scope of practice

The following resources expand on the information contained in this article.

Articles on the appropriate use of touch as a component of communication:

- ‘Touch in mental health nursing: an exploratory study of nurses’ views and perceptions‘;

- ‘From SOLER to SURETY for effective non-verbal communication‘;

- ‘Touch in primary care consultations: qualitative investigation of doctors’ and patients’ perceptions‘.

Resources supporting the use of the Calgary-Cambridge consultation model:

- National Healthcare Communication Programme;

- Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., and Draper, J. Skills for communicating with patients, 3rd edition. 2013. New York, Taylor and Francis Group.

- 1Standards for pharmacy professionals. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2017. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf (accessed October 2023)

- 2The Code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. Nursing and Midwifery Council. 2018. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/ (accessed October 2023)

- 3Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. Health and Care Professionals Council. 2016. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/resources/standards/standards-of-conduct-performance-and-ethics/ (accessed October 2023)

- 4Professional standards for doctors. General Medical Council. 2013. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors (accessed October 2023)

- 5Activity in the NHS. The Kings Fund. 2023. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/NHS-activity (accessed October 2023)

- 6Bailo L, Guiddi P, Vergani L, et al. The patient perspective: investigating patient empowerment enablers and barriers within the oncological care process. ecancer. 2019;13. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2019.912

- 7Cerezo PG, Juvé-Udina M-E, Delgado-Hito P. Concepts and measures of patient empowerment: a comprehensive review. Rev. esc. enferm. USP. 2016;50:667–74. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0080-623420160000500018

- 8Health 2020: a European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. World Health Organization. 2013. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326386 (accessed October 2023)

- 9A Competency Framework for all Prescribers. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2021. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks/prescribing-competency-framework/competency-framework (accessed October 2023)

- 10Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. 3rd ed. New York: Taylor and Francis Group 2013.

- 11Al-Jabr H, Twigg MJ, Scott S, et al. Patient feedback questionnaires to enhance consultation skills of healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2018;101:1538–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.016

- 12Leach MJ. Rapport: A key to treatment success. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2005;11:262–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.05.005

- 13English W, Gott M, Robinson J. The meaning of rapport for patients, families, and healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2022;105:2–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.06.003

- 14Summerton N. The medical history as a diagnostic technology. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:273–6. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08x279779

- 15Hampton JR, Harrison MJ, Mitchell JR, et al. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. BMJ. 1975;2:486–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.5969.486

- 16Bickley L. Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2020.

- 17Becker MH, Maiman LA. Sociobehavioral Determinants of Compliance with Health and Medical Care Recommendations. Medical Care. 1975;13:10–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-197501000-00002

- 18Neighbour R. The Inner Consultation. Lancaster, Lancashire: MTO Press 1987.

- 19Pendelton D, Schofield T, Tate P, et al. The Consultation: An Approach to Learning and Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1984.

- 20NHS Long Term Plan. NHS. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed October 2023)

- 21Denness C. What are consultation models for? InnovAiT. 2013;6:592–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755738013475436

- 22Langewitz W. Spontaneous talking time at start of consultation in outpatient clinic: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:682–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7366.682

- 23Collins LC, Gablasova D, Pill J. ’Doing Questioning’ in the Emergency Department (ED). Health Communication. 2022;38:2721–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2111630

- 24Taylan C, Weber LT. “Don’t let me be misunderstood”: communication with patients from a different cultural background. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;38:643–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05573-7

- 25Spoken communication and patient safety in the NHS. NHS England. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/spoken-communication-and-patient-safety-in-the-nhs/ (accessed October 2023)

- 26Egan G. The Skilled Helper: A Systematic Approach to Effective Helping. California, USA: Brooks/Grove 1975.

- 27Stickley T. From SOLER to SURETY for effective non-verbal communication. Nurse Education in Practice. 2011;11:395–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.03.021

- 28Cocksedge S, George B, Renwick S, et al. Touch in primary care consultations: qualitative investigation of doctors’ and patients’ perceptions. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e283–90. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13x665251

- 29Van den Brink N, Holbrechts B, Brand PLP, et al. Role of intuitive knowledge in the diagnostic reasoning of hospital specialists: a focus group study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e022724. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022724

- 30Byrne P, Long B. Doctors talking to patients : a study of the verbal behaviour of general practitioners consulting in their surgeries. London: HMSO 1976.

- 31Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. 2nd ed. London: Pitman Medical 1986.

- 32Merrill D, Reid R. Personal Styles and Effective Performance: Make Your Style Work for You. NHS England. 1999. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/qsir-understand-differences-between-individuals.pdf (accessed October 2023)

- 33Lucas P. Critical reflection: what do we really mean? . 2012.