Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Describe some of today’s main strategic drivers and priorities;

- Highlight case examples of innovative pharmacy practice;

- Use self-care tips to manage professional challenges more effectively.

Introduction

Integrating strategic priorities into practice is crucial to aligning healthcare delivery with organisational goals and improving patient experience and outcomes. This requires a comprehensive approach, translating broad strategic objectives into actionable steps that directly benefit patient care. This article will explore the methodologies and strategies pharmacy professionals can employ to seamlessly integrate strategic priorities into their clinical practice.

The ‘NHS long term plan’, published in 2019, sets out a vision for the future of the NHS in England, outlining priorities and strategies for addressing healthcare challenges and improving patient care over the coming years[1]. It focuses on areas such as workforce, illness prevention, digital innovation and integration of services to ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of the NHS in meeting the evolving needs of the population.

Published in June 2023, ‘The NHS in England at 75: Priorities for the Future’ report identified three shifts that were needed to respond to the continuing rise of chronic ill-health and frailty, the need for people to have greater involvement in their health and wellbeing, and the opportunities offered by new technology, data, and modern forms of care (see Table 1)[2].

NHS integrated care systems (ICSs) were established in July 2022, replacing clinical commissioning groups[3]. However, the concept of integrated care and collaboration among healthcare organisations has been evolving for many years, with various models and initiatives preceding the formal creation of ICSs. ICSs enable the NHS to collaborate with external organisations to tackle major causes of poor health, such as obesity and smoking, while also targeting individuals at risk of conditions such as heart disease, aligning with the theme of preventing ill health[4].

Poor health and outcomes are linked to socioeconomic status and deprivation (the wider determinants of health)[5]. Pharmacy teams in every setting have an essential role in public health and disease prevention, such as providing smoking cessation services, health coaching and vaccinations[6]. By working in close collaboration with other healthcare professionals, pharmacy professionals can provide comprehensive medicines optimisation, preventative care, health promotion and disease management services[7].

National strategic priorities within the NHS and the role of pharmacy

The ‘NHS Long Term Workforce Plan’, published in 2023, has three main themes: train, retain and reform[8]. Investing in the workforce is important to build competence and confidence. A robust workforce means patients can be optimally managed, with greater partnership working between healthcare services and timely referral to relevant specialist services where required. It is also important for retention and succession planning.

The 2024/2025 priorities and operational planning guidance highlight 12 areas and 31 objectives for integrated care boards (ICBs) to work with their systems partners to meet[9].

How to engage with strategy and long-term plans in practical steps

There are several innovative ways pharmacy teams can work inclusively across sectors: shared employment models and cross-sector working; group consultations including the patient’s wider healthcare team; care closer to home; and taking a population health management approach. These approaches will be vital going forward to join up pharmacy care, closing the loop across settings to provide assurance of our upcoming novice pharmacist prescriber workforce and deliver cost-effective clinical care.

The steps below will help you translate strategic plans into practical action in pharmacy practice.

Step 1: Understand the strategic aims

Familiarise yourself with the main objectives and priorities outlined in the NHS long term plan, including prevention, reducing health inequalities and enhancing patient care[1]. Other helpful documents include local ICB plans, such as pharmaceutical needs assessments, national medicines optimisation opportunities and relevant policy updates[9]. You could attend webinars (such as those hosted by the Specialist Pharmacy Service or The Health Foundation), read NHS newsletters, and participate in professional development courses to stay informed.

Step 2: Contextualise the strategy for your sector, role and local area

Identify how the strategic aims apply specifically to your setting and area of practice, as the areas of focus will differ. One approach is to undertake a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis to understand how your role fits within the broader strategic framework. This can be used as a foundation for discussion with colleagues and supervisors to gain different perspectives on how to apply these aims locally.

Step 3: Be active in stakeholder engagement

Actively engage with multiprofessional stakeholders, such as other healthcare teams, local authorities, voluntary/charity sector groups, and patient groups to ensure collaboration. You could attend local health board meetings, join professional forums, and participate in multidisciplinary teams to stay informed and contribute to discussions.

Step 4: Identify opportunities for implementation

Look for specific initiatives or programmes that align with the strategic goals that can be implemented in your practice. As a team, consider where there may be potential for pilot projects, collaboration on research initiatives, or adaptation of successful models from other areas. Another approach is to develop patient education materials that align with the strategic priorities, such as leaflets on preventive health measures or videos on managing chronic conditions.

Step 5: Take a quality improvement approach

Use quality improvement methodology to implement the identified strategies and monitor the impact on patient outcomes and service delivery. Collect data and feedback to evaluate the effectiveness of changes. Develop key performance indicators to measure success, such as patient satisfaction scores, reduction in medication errors, or improved adherence rates. Regularly review and report on these metrics to stakeholders to continue to develop and refine your ideas.

Prevention and health inequalities

The Core20PLUS5 is an approach outlined by NHS England to reduce healthcare inequalities — one of the five clinical areas is ‘hypertension case-finding and optimal management and lipid optimal management’[10]. One of the national objectives is to continue to address health inequalities, deliver on the Core20PLUS5 approach and allow for interventions to minimise the risk of heart attacks and strokes[9].

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is strongly correlated with health inequalities. People living in deprived areas are four times more likely to die prematurely from preventable or treatable conditions than people living in more affluent areas[11]. The CVD recovery plan was designed to meet the NHS’s ambition in the long-term plan of preventing up to 150,000 heart attacks, strokes, and dementia cases by 2029[1,12].

Box 1: Case study – primary care pharmacy team, Barts Health NHS Trust

A pharmacist-led service was developed to improve anticoagulation and address other cardiovascular risk factors in eligible patients with atrial fibrillation in all general practices in a London borough[13]. The service has since expanded beyond that borough to reviewing patients in the community at high risk of CVD and optimising their lipid-lowering therapies[14].

This model of care involves specialist pharmacists from a tertiary cardiac centre working alongside primary care clinicians (predominantly pharmacy professionals) to identify high-risk CVD patients, enabling access to medicines. Data from the Clinical Effectiveness Group at Queen Mary University of London and national tools, such as CVDPREVENT, with health inequality insights, guide the team to optimise therapies holistically, close to home. Between 2020 and 2023, this medicines optimisation has translated into the prevention of 34 strokes and 14 heart attacks[15].

This model shows how integrating pharmacy can support a whole-system approach to medicines optimisation, improve population health and address health inequalities[16].

People with a learning disability or autism

Another national objective is to reduce reliance on inpatient care while improving the quality so that by March 2024, no more than 30 adults with a learning disability and/or autism per million adults, and no more than 12–15 under 18s with a learning disability and/or autism per million under 18s, are cared for in an inpatient unit[9].

Six in ten people with learning disabilities die before the age of 65 years, compared with one in ten of the general population[17]. The Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism is recommended by the government for health and social care staff, including pharmacy professionals (see Figure 1)[18]. The death of Oliver McGowan in hospital highlighted the need for health and social care staff to have better skills, knowledge and understanding of the needs of autistic people and people with learning disabilities[19].

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Pharmacy teams in community, primary care and acute hospital settings see many people with learning disabilities[20]. Pharmacy professionals can complete the ‘Learning disabilities’ distance learning programme from the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education to learn how to actively support people with learning disabilities[19].

The Islington Learning Disabilities Partnership is an example of how pharmacy teams can proactively support adults with learning disabilities[21]. The partnership includes a clinical pharmacist, who provides information, advice and support to local people with learning disabilities, as well as their families, carers and social care staff teams, and health and social work colleagues in the integrated community team[21]. They also liaise with community pharmacists[21].

Care closer to home (or at home)

Virtual wards aim to treat people in the comfort of their home while maintaining their independence[22]. In addition, they support the NHS’s delivery plan to address the recovery of primary care after the COVID-19 pandemic and enable reforms to the way hospital care is provided[23]. The use of virtual wards supports the NHS long term plan by relieving pressure elsewhere in the hospital and freeing up beds for patients who need admission, either for emergency care or for a planned operation[24].

Virtual wards offer an opportunity to address healthcare inequalities in target areas, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and frailty[25]. Socioeconomic deprivation negatively impacts health and outcomes[5]. Despite COPD being more common in deprived communities, COPD services are often used less in these areas. The ‘inverse care law’ states that those who need care the most are often the least likely to receive it, resulting in increased morbidity and health inequalities[26,27]. Virtual wards offer equal access across communities to integrated input from pharmacists, therapists and other specialties[25]. Pharmacy teams should participate in virtual ward rounds, multidisciplinary team meetings and patient reviews as appropriate for the needs of the patient[28]. A personalised approach should be taken, with a focus on addressing health inequalities[29].

As suggested in the article ‘The virtual ward pharmacist: a new breed’, pharmacy teams can contribute to the care of patients in virtual wards by carrying out structured medication reviews (remotely or by home visit), giving advice on potential interactions, adverse effects that might be contributing to the acute illness, and the best medicines, as well as liaising with community pharmacies, patients and their carers about the optimal way to deliver the medicines to them[30].

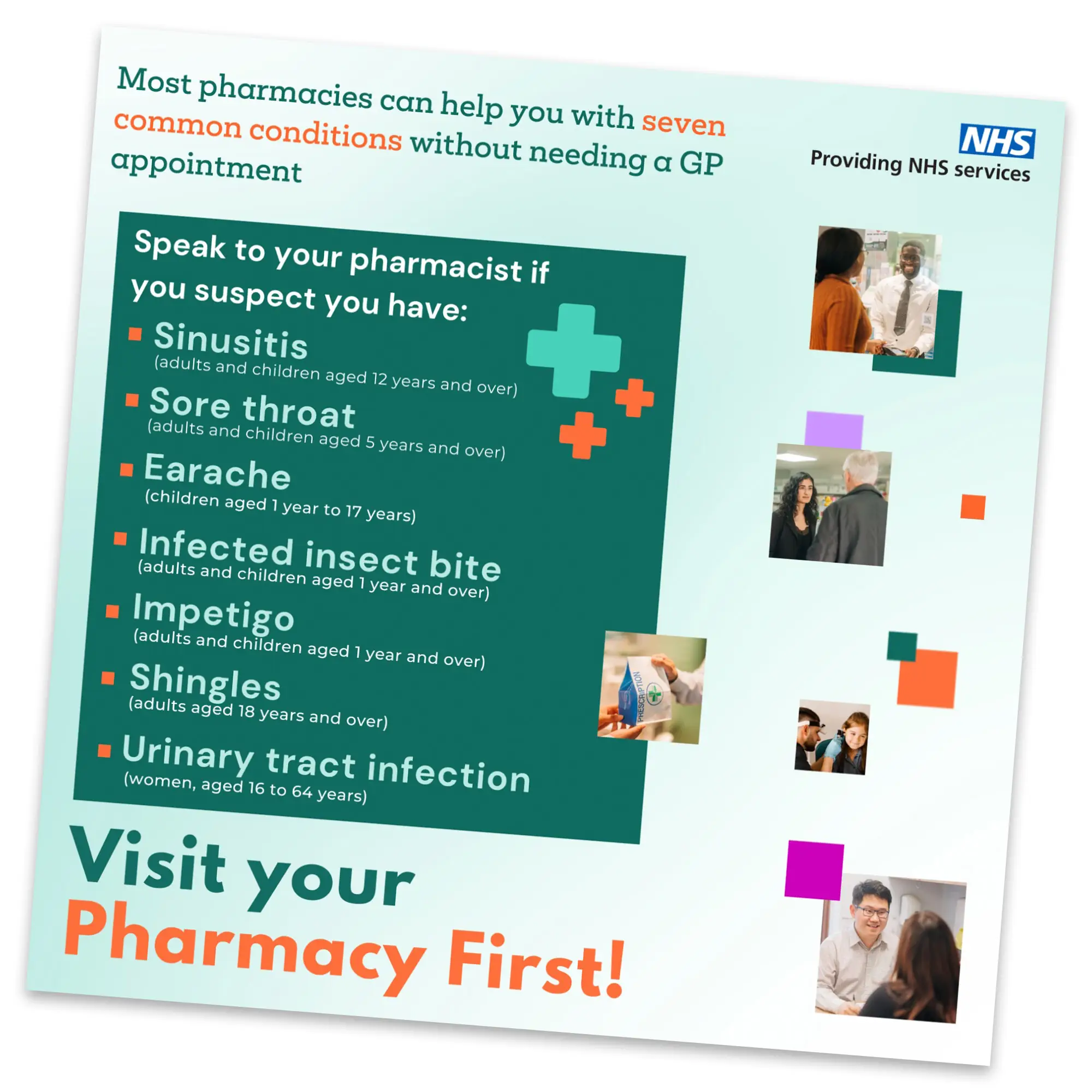

Primary care

A crucial component of the NHS’s urgent and emergency care recovery plan is to encourage people to use community pharmacies, particularly through expanding clinical services related to oral contraception and blood pressure, alongside the recent launch of the Pharmacy First service on 31 January 2024 (see Figure 2)[23,31].

It is anticipated that these initiatives will alleviate pressure on general practice by saving approximately 10 million appointments annually, consequently freeing up GP time[31]. The Pharmacy First service is poised for further development with the upcoming cohort of pharmacy graduates in 2026 qualifying as independent prescribers[31].

The next phase will involve NHS England’s ‘pathfinder’ sites within ICBs, aiming to explore how community pharmacy independent prescribers can further support primary care by offering clinical services tailored to local community needs[32]. As central pillars of their intergrated neighbourhood teams, community pharmacy is uniquely well placed to deliver not only clinical services but also initiatives aimed at preventing illness and enhancing wellbeing.

NHS England

Another strategic priority in England is the integration of specialised services within ICBs. A ‘roadmap’ for this was published by NHS England in May 2022[33]. From April 2024, some specialised services are being delegated to ICBs; for example, severe asthma[33]. The aims of delegation are twofold: to enable greater access to specialised care and treatment for patients who need it and to build capability within the system[33,34].

Anecdotally, we know many patients remain in primary care with ‘uncontrolled’ asthma and have not had their management fully reviewed and optimised. Those with truly uncontrolled disease (even after management plans are reviewed) in either primary or secondary care usually require optimisation, further specialist input and, in some cases, potentially biologic treatment[35]. These patients often have long delays to referral and specialist care, and delays are usually associated with high cumulative oral corticosteroid and antimicrobial agent exposure and associated poor health-related quality of life (including worsening of mood and other comorbidities). More information can be found in: ‘Improving the management of uncontrolled asthma for adults in England: where do pharmacists fit?’.

A project in south west London highlights the success of specialist advanced/consultant pharmacists working in a more integrated way and can be applied to other long-term conditions (Box 2).

Box 2: Case study — respiratory disease project

A collaborative project in south west London, between a GP surgery and Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust, was developed to review and address the problem of respiratory disease. Respiratory disease and outcomes in the UK are very poor compared with European countries[36,37].

A specialist respiratory pharmacist conducted reviews of patients with uncontrolled lung disease and high use of short-acting beta agonists (SABAs) in primary care. The majority of these patients had not undergone full medication optimisation and were not using their medications correctly, if at all. Through targeted face-to-face reviews, the specialist pharmacist achieved improved medication adherence, provided lifestyle and holistic advice, addressed potential misdiagnoses and optimised medication regimens (leading to reduced SABA usage and, in some cases, deprescribing). This approach also resulted in increased patient satisfaction and two referrals to specialist care.

Pharmacists are a vital part of the multidisciplinary team. By developing their skills and credentialing as advanced or consultant-level practitioners, via the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) in specialist areas or advanced core practice, they are able to provide more clinical leadership, add value to teams and enhance patient care and experience[38]. It will be especially important to develop and strengthen local infrastructure and integrate care as pharmacy professional roles continue to extend and evolve.

Investing in our workforce

The NHS long term workforce plan emphasises the importance of investing in its workforce to meet changing patient needs[8]. The plan seeks to address the growing demand for pharmacy services. Specifically, the plan aims to significantly expand education and training opportunities for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, with the goal of increasing training posts by nearly 50% to approximately 5,000 places by 2031/2032[8].

While training is crucial, a supportive workplace culture is equally essential to retaining staff and addressing vacancy challenges. Cultivating a culture of compassion and inclusion is essential, and initiatives such as Inclusive Pharmacy Practice (IPP) are instrumental in this regard. IPP is a collaborative effort, involving organisations such as the RPS and the Association of Pharmacy Technicians UK, focusing on creating more inclusive pharmacy workplaces[39]. A talent management resource tool that sets out development and leadership opportunities for pharmacy professionals across sectors has been developed as part of the initiative[39]. This tool was produced to ensure that all pharmacy professionals have equal access to opportunities for career advancement.

A notable example of regional implementation is the ‘Inclusive Pharmacy Practice Manifesto’ in south west England[40]. Aligned with national IPP principles and the NHS’s equality, diversity, and inclusion improvement plan, the manifesto outlines five principles:

- Education and training;

- Recruitment and retention;

- Pre-employment support;

- Reflective learning processes;

- Inclusive leadership.

It aims to support employers and organisations in the region in implementing inclusive practices in their pharmacies.

Workload pressures and burnout

Although these initiatives are positive, they will place additional burden on pharmacy teams’ workloads; therefore, it is important that pharmacists are supported to manage this additional work. The 2023 Workforce and Wellbeing Survey, conducted by the RPS and charity Pharmacist Support, indicated that 86% of the profession is at risk of burnout and that 60% of people have considered leaving their role or the pharmacy profession[41].

Risk factors for poor wellbeing in pharmacy include working longer hours, increased workload, poor work-life balance, lack of protected learning time, lack of burnout management resources, too many non-clinical/administrative duties and a lack of appreciation from colleagues and the public[42].

These issues will need to be addressed if the incorporation of strategic priorities into clinical practice is to be successful. Some practical ways that pharmacists can help to decrease burden and improve their own wellbeing are:

- Learn how to delegate effectively — make a list of all current tasks and determine which could be performed by others;

- Train others instead of taking on additional work — it can become a habit to take on others’ work because it seems quicker to do the task yourself rather than spend the time training others. However, this only leads to an ever-increasing workload. By investing the time to train other individuals, not only does this help their development, but it will lead to a decrease in stress levels across the team.

- Swap self-criticism for self-compassion — striving for perfection can lead to holding overly high standards for ourselves and others. If those standards are not met, it can lead to intense self-criticism, which in turn impacts self-confidence. A more impactful way to self-motivate is to come from a place of self-compassion instead. Consider what you might say if a colleague was experiencing the same situation to encourage and motivate them.

- Try not to compare yourself to others — continual comparison to others also leads to additional stress and anxiety. Remember that every individual deals with workload pressures in a different way and there is no ‘right way’. Mentors and coaches are helpful in achieving career aspirations and can also provide a fresh perspective on challenges. The RPS offers a mentoring platform, where pharmacy professionals are able to find a suitable mentor to develop their career[43].

Conclusion

Incorporating strategic priorities into clinical practice is essential for pharmacy professionals to align with the broader objectives of the NHS and improve patient outcomes. By understanding and engaging with national plans, such as the NHS long term plan and the NHS long term workforce plan, pharmacy teams can contribute significantly to healthcare delivery. Practical strategies, such as collaborating across sectors, focusing on prevention, and utilising data-driven approaches, are vital to addressing health inequalities and enhancing patient care. Moving forward, pharmacy teams must remain adaptable, continuously seeking opportunities for innovation and improvement to meet the evolving needs of the healthcare landscape.

- 1The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS England. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ (accessed July 2024)

- 2The NHS in England at 75: priorities for the future. NHS Assembly. 2023. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/The-NHS-in-England-at-75-priorities-for-the-future.pdf (accessed June 2024)

- 3Dunn P, Fraser C, Williamson S, et al. Integrated care systems: what do they look like? The Health Foundation. 2022. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/integrated-care-systems-what-do-they-look-like?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwqpSwBhClARIsADlZ_TmG-21V1i1ULeyERMJIU665dP7q99OUxBs5vm-ETAnno6CfljqvYEcaAm0AEALw_wcB (accessed July 2024)

- 4Helping People Stay Well and Greater Use of Tech to Empower Patients Should be Central to NHS Plans. NHS England. 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2023/06/helping-people-stay-well-and-greater-use-of-tech/ (accessed July 2024)

- 5Marmot M, Allen J, Boyce T, et al. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. The Health Foundation. 2020. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on (accessed July 2024)

- 6RPS Recommendations for Integrated Care Systems. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2024. https://www.rpharms.com/england/nhs-transformation/ics-recommendations (accessed July 2024)

- 7Patel H. Community pharmacy has much to contribute to the goals of the ‘NHS long-term plan’. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/opinion/community-pharmacy-has-much-to-contribute-to-the-goals-of-the-nhs-long-term-plan#:~:text=The%20’NHS%20long%2Dterm%20plan’%20recognises%20the%20significance%20of,prescribers%20to%20optimise%20medication%20regimens (accessed July 2024)

- 8NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan/ (accessed July 2024)

- 92024/25 Priorities and Operational Planning Guidance. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024-25-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance-v1.1.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 10Core20PLUS5 (adults) – an approach to reducing healthcare inequalities. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/ (accessed July 2024)

- 11Health matters: preventing cardiovascular disease. Public Health England. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease (accessed July 2024)

- 12Cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention recovery. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/cvd/prevention-recovery/ (accessed July 2024)

- 13Chahal JK, Antoniou S, Earley M, et al. Preventing strokes in people with atrial fibrillation by improving ABC. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000783.

- 14Lipid Optimisation Programme: Redbridge, North-East London. NHS Barts Health NHS Trust. 2023. https://www.heartuk.org.uk/downloads/health-professionals/tackling-cholesterol-together/north-east-london-lipid-optimisation-programme.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 15CVDPREVENT. NHS England. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/cvd/cvdprevent/ (accessed July 2024)

- 16Integrating NHS Pharmacy and Medicines Optimisation into Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships and Integrated Care Systems. NHS England. 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ipmo-programme-briefing.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 17White A, Sheehan R, Ding J, et al. Learning from Lives and Deaths – People with a Learning Disability and Autistic People. King’s College London. 2022. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/assets/fans-dept/leder-2022-v2.0.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 18The Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism. NHS England. 2023. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/learning-disability/current-projects/oliver-mcgowan-mandatory-training-learning-disability-autism (accessed July 2024)

- 19Anderson E, Gerrard D. Learning disabilities: a CPPE distance learning programme. Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. 2016. https://www.cppe.ac.uk/learningdocuments/pdfs/cppe_learningdisabilities_2.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 20Pharmacy and people with learning disabilities: making reasonable adjustments to services. Public Health England. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pharmacy-and-people-with-learning-disabilities/pharmacy-and-people-with-learning-disabilities-making-reasonable-adjustments-to-services (accessed July 2024)

- 21Learning Disabilities Partnership. North Central London Integrated Care Board. 2024. https://gps.northcentrallondon.icb.nhs.uk/services/islington-learning-disabilities-partnership-ildp (accessed July 2024)

- 22Supporting information: Virtual ward including Hospital at Home . NHS England. 2022. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/B1478-supporting-guidance-virtual-ward-including-hospital-at-home-march-2022-update.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 23Urgent and emergency care recovery plan year 2: building on learning from 2023/24. NHS England. 2024. www.england.nhs.uk/publication/urgent-and-emergency-care-recovery-plan-year-2-building-on-learning-from-2023-24/ (accessed July 2024)

- 24How to develop a new clinical service. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023.

- 25Making the Most of Virtual Wards, Including Hospital at Home. Getting It Right First Time and NHS England Virtual Ward Programme. NHS England. 2023. https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Making-the-most-of-virtual-wards-incl-heart-failure-FINAL-V2-November-2023.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 26Fisher R, Allen L, Malhotra A, et al. Tackling the inverse care law. The Health Foundation. 2022. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/tackling-the-inverse-care-law (accessed July 2024)

- 27Calderon-Larranaga A, Carney L, Soljak M, et al. Association of population and primary healthcare factors with hospital admission rates for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in England: national cross-sectional study. Thorax. 2010;66:191–6.

- 28Guidance on Pharmacy Services and Medicines Use within Virtual Wards (including Hospital at Home). NHS England. 2022. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Guidance%20on%20Pharmacy%20Services%20and%20Medicines%20Use%20within%20Virtual%20Wards%20_including%20Hospital%20at%20Home%20%281%29.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 29Supporting Clinical Leadership within Virtual Wards – A Guide for Integrated Care System Clinical Leaders. NHS England. 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/supporting-clinical-leadership-in-virtual-wards-a-guide-for-integrated-care-system-clinical-leaders/ (accessed July 2024)

- 30The virtual ward pharmacist: a new breed. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023.

- 31Pharmacy First. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/pharmacy-services/pharmacy-first/ (accessed July 2024)

- 32Independent prescribing. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/pharmacy-integration-fund/independent-prescribing/ (accessed July 2024)

- 33Roadmap for Integrating Specialised Services within Integrated Care Systems. NHS England. 2022. PAR1440-specialised-commissioning-roadmap-addendum-may-2022.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 34From delegation to integration: lessons from early delegation of primary pharmacy, optometry and dentistry commissioning to integrated care boards. NHS Confederation. 2023. https://www.nhsconfed.org/publications/delegation-integration (accessed July 2024)

- 35Consensus pathway for managing uncontrolled asthma in adults. Health Innovation Oxford and Thames Valley. 2022. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/our-work/respiratory/asthma-biologics-toolkit/aac-consensus-pathway-for-management-of-uncontrolled-asthma-in-adults/ (accessed July 2024)

- 36Why asthma still kills. Royal College of Physicians. 2016. https://www.rcp.ac.uk/improving-care/resources/why-asthma-still-kills/ (accessed July 2024)

- 37APPG Report: Improving Asthma Outcomes in the UK – One Year On. All Party Parliamentary Group for Respiratory Health. 2022. https://www.appg-respiratory.co.uk/sites/appg/files/2022-02/APPG-Asthma-Report-2022.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 38Credentialing. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2024. https://www.rpharms.com/development/credentialing (accessed July 2024)

- 39Inclusive Pharmacy Practice. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/inclusive-pharmacy-practice/ (accessed July 2024)

- 40South West SPMs Inclusive Pharmacy Practice (IPP) sub-group. Pharmacy Workforce Development South. 2024. https://pwds.nhs.uk/networks/south-west-spms-inclusive-pharmacy-practice-ipp-sub-group/ (accessed July 2024)

- 41Workforce and Wellbeing Survey 2023 Survey analysis by the RPS Research Team. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2023. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Workforce%20Wellbeing/Workforce%20and%20Wellbeing%20Survey%202023-007.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 42Workforce Wellbeing Roundtable Report. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2023. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Workforce%20Wellbeing/Workforce%20Wellbeing%20Roundtable%20Report%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed July 2024)

- 43Mentoring. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2024. https://www.rpharms.com/development/mentoring (accessed July 2024)